Wanting to learn more facts and information about Hong Kong? China Mike has you covered with this article that will answers some questions you may have.

OPIUM ADDICTION

Until the British started importing opium, foreign trade with China was severely one-way. The European traders couldn’t get enough tea, silk, and porcelain. However, the Chinese were indifferent to woolens, furs, and spices offered by the “red haired barbarians”. The result was that the Chinese imported little—while vast amounts of silver flowed into China.

As the British became hooked on tea and other Chinese imports, they needed to find a solution to their growing trade deficit.

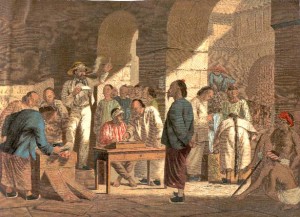

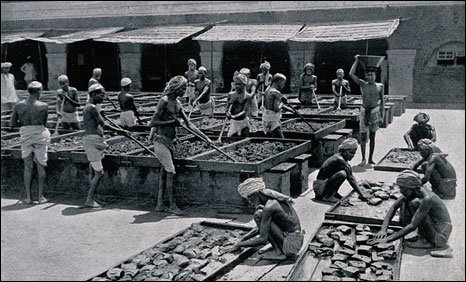

1773: The trade situation starts to reverse after the British East India Company secures a monopoly on opium, which it sold to British merchants at auction in Calcutta. During that first year, the British imported 200 chests, each containing 160 pounds of Bengali opium.

1799: China’s consumption reaches 2,000 chests a year. The Emperor Jiaqing bans the opium trade completely. But neither British merchants nor Guangdong merchants growing rich on it were ready to give it up.\

The opium ban is easily circumvented with a never-ending stream of greedy and corrupt local Chinese officials, who became part of the smuggling network. Clippers arriving in Canton simply unloaded the contraband onto floating stores before heading into port for customs inspections; the opium was later smuggled ashore.

William Jardine (1784-1843)— head of the preeminent hong Jardine, Matheson and Company—glibly commented that since “opium is the only real money article sold in China,” it had to be smuggled in.

Between 1810-1830, opium use became widespread in China—annual shipments increased from 5,000-23,000 chests. At the height, there were an estimated one million opium addicts in China, from coolies and ordinary Chinese to traders and rich merchants to soldiers and government officials.

1825: Opium imports push China’s trade balance into the red.

1830s: Huge outflow of silver used to pay for opium leads to a major economic crisis. The illicit opium trade becomes the most controversial issue between the Chinese government and the British traders at Canton.

1840-1842: THE (FIRST) OPIUM WAR

The Opium War had tremendous impact on China—opening it to Western influences as traditional Chinese values began to change after the war.

1839: The Qing government gets tough on opium. Emperor Daoguang appoints Lin Zexu (1785-1850), a high-ranking official, to stop the problem. His soldiers lays siege to the hongs’ factories and stopped food supplies for six weeks before the British—under the command of Captain Charles Elliot (1801-1875) —hands over more than 20,000 chests of opium.

The opium is dumped into the trenches by a river, mixed with lime, and flushed out to sea. The British stops all trade with China and head for Macau. Hostilities build until November 1839, when British ships blow up four Chinese junks, sparking the first Opium War.

June 1840: A British expeditionary force of 4,000 blockades Canton. Negotiations break down and the British fleet attacks Canton and occupies the city’s forts—killing around 600 Chinese soldiers.

Under increasing threat of Britain’s superior naval power, the Chinese finally agree to a draft treaty in January 1841 (the Convention of Chuen Pi), which cedes Hong Kong to the British.

January 26, 1841: Wasting no time, the British raise their flag at Possession Point on Hong Kong island. Five months later, British officials began selling plots of land and the colonization of Hong Kong began.

But both sides were unhappy with the treaty. British Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerson blasts Captain Elliot for failing to extract more concessions. Elliot is recalled in disgrace and replaced by Sir Henry Pottinger (1801-1875).

GUNBOAT DIPLOMACY & THE TREATY OF NANKING

British forces besiege Guangzhou before sailing north and occupying or blockading a number of ports and cities along the Yangtze River and the coast. After Shanghai fell to the British and Nanking was threatened, Qing authorities finally gave in to demands.

August 29, 1842: The Treaty of Nanking is signed, abolishing the monopoly system of trade. The treaty awards Britain 21 million ounces of silver in compensation for the seized opium, and opens five Chinese coastal ports to British trade: Canton, Amoy (today’s Xiamen), Fuzhou, Ningbo, and Shanghai (the first of the “treaty ports”).

The treaty also confirms the British possession of Hong Kong, which is formally transferred to Britain “in perpetuity”. Pottinger becomes the first British governor of Hong Kong.

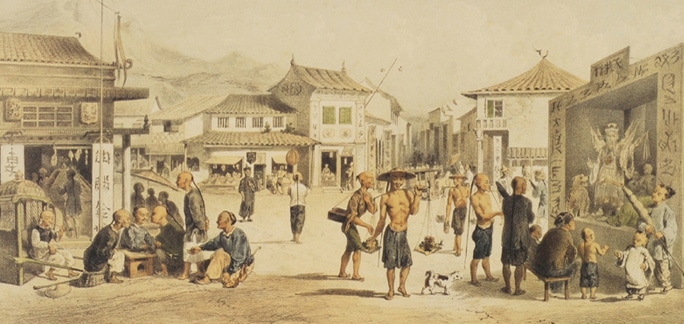

Hong Kong becomes the first Chinese territory to be taken by a Western power. Suddenly, China was exposed to a new and troublesome “enemy at the gate”. As Portuguese power in Asia continue to weaken, Hong Kong began its growth as one of the greatest port cities the world has ever seen.

WHY HONG KONG?

When Hong Kong became part of Queen Victoria’s dominions in 1841, she was amused by the notion that her daughter Princess Victoria Adelaide Mary Louise might become the “Princess of Hong Kong.”

On the other hand, foreign secretary Palmerson was “greatly mortified and disappointed”– famously calling Hong Kong “a barren island with barely a house on it”. He and other British officials were interested in greater spoils along Chinas prosperous coast. Specifically, they wanted Chusan, a bustling trade port at the mouth of the Yangzi River.

But the British traders at Canton and Captain Elliot (who was also the Superintendent of Trade in Canton since 1835) recognized the strategic advantages of Hong Kong (which came from the Cantonese name hèung-gáwng, meaning “fragrant harbor’”)

As early as 1836, a correspondent had written in the April issue of the Canton Register that “If the British lion’s paw (were) to be put down on any part of the south side of China, let it be Hong Kong”. Specifically, they realized that Hong Kong’s strategic geographical location—combined with its deep and sheltered harbor—made it an ideal location for trade between China and Southeast Asia….and the rest of the world.