THE COLLAPSE OF EMPIRE [ 1842-1911 ]

In the second half of 19th century, China was called “the sick man of Asia”. Karl Marx said that China was bound to disintegrate when it met the glare of outside light, like “any mummy carefully preserved in a hermetically sealed coffin.”

But once again, history’s turbulence contained the seed of regeneration. China was pulled—kicking and screaming—into the modern world. New ideas and technology were slowly absorbed. By the end of the 19th century, railways, steamboats, and telegraph wire were familiar sights to many Chinese.

CHINESE EMIGRATION

Starting in the 1840’s — with the introduction of steamboats — hundreds of thousands of Chinese left China in search for a better life. For instance, the California gold rush (1848-49) drew many to the west coast of America. By 1880, there were 100,000 Chinese spread out in US (but in 1882, anti-Chinese laws passed and abruptly shut off immigration).

Starting in the 1840’s — with the introduction of steamboats — hundreds of thousands of Chinese left China in search for a better life. For instance, the California gold rush (1848-49) drew many to the west coast of America. By 1880, there were 100,000 Chinese spread out in US (but in 1882, anti-Chinese laws passed and abruptly shut off immigration).

A SOLUTION TO THE TRADE DEFICIT…

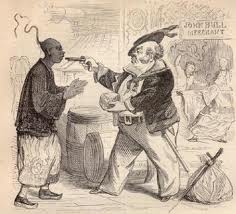

Meanwhile, the problem remained for the British: How to pay for all of this tea? Britain soon found the solution in India, where it was firmly established by 1800. It was there that they developed a rival export commodity with even greater “therapeutic” properties: the OPIUM poppy.

Meanwhile, the problem remained for the British: How to pay for all of this tea? Britain soon found the solution in India, where it was firmly established by 1800. It was there that they developed a rival export commodity with even greater “therapeutic” properties: the OPIUM poppy.

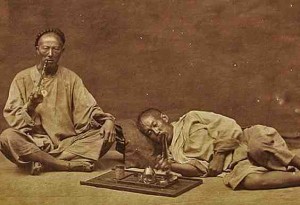

Describing opium’s destructive addictive properties, a popular saying of the time was: “The hole of an opium pipe is as small as a needle, but you can put a water buffalo in it and you can also smoke hundreds of mu of land through it.”

1820-30’s: The opium trade snowballs. Silver starts to pour out of China. By 1825, opium imports push China’s trade balance into the red.

The Qing government declare opium illegal and try unsuccessfully to stamp it out for decades. But without an effective navy, they couldn’t stop British traders. The law was ignored by the Chinese too—which wasn’t helped by the fact that an estimated 20% of officials were also smoking it (reminds me of the No Smoking signs ignored by Chinese men today!).

The Qing government declare opium illegal and try unsuccessfully to stamp it out for decades. But without an effective navy, they couldn’t stop British traders. The law was ignored by the Chinese too—which wasn’t helped by the fact that an estimated 20% of officials were also smoking it (reminds me of the No Smoking signs ignored by Chinese men today!).

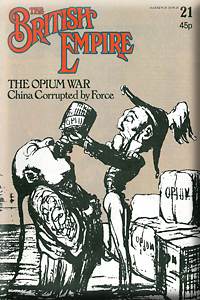

THE OPIUM WAR: GUNBOAT DIPLOMACY AT ITS FINEST

In 1839, the Qing got tough on opium—dumping 3 million pounds of opium into the sea. Britain responded by blockading the port of Guangzhou and sinking several Chinese war junks. The (first) Opium War started.

In 1839, the Qing got tough on opium—dumping 3 million pounds of opium into the sea. Britain responded by blockading the port of Guangzhou and sinking several Chinese war junks. The (first) Opium War started.

Britain’s superior weaponry took the Qing by complete surprise. British cannons were able to fire with impunity, from far away at sea. It was over quickly—a complete, one-sided ass-whooping by the British navy, and a humiliating defeat for the Qing. Not since the Mongols had China been so thoroughly driven into submission.

The war was over with the signing of the Treaty of Nanjing in 1842 (the first of several “unequal treaties”). The Qing was forced to pay the British 21 million silver dollars and open five cities as “treaty ports” (Guangzhou, Fuzhou, Xiamen, Ningbo and Shanghai). The treaty also ceded Hong Kong to the British. Significantly, foreigners were also given “extra-territorial rights,” which prevented Chinese government from prosecuting any foreigners who committed crimes (instead would be tried by foreign courts in China).

The war was over with the signing of the Treaty of Nanjing in 1842 (the first of several “unequal treaties”). The Qing was forced to pay the British 21 million silver dollars and open five cities as “treaty ports” (Guangzhou, Fuzhou, Xiamen, Ningbo and Shanghai). The treaty also ceded Hong Kong to the British. Significantly, foreigners were also given “extra-territorial rights,” which prevented Chinese government from prosecuting any foreigners who committed crimes (instead would be tried by foreign courts in China).

[ For more on the history of HK, see my Hong Kong History for Dummies, part 1-5 ]

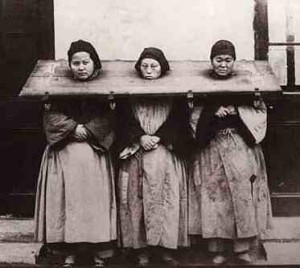

A REALITY CHECK: WE’RE (NOT) #1!

Curiously, the treaty didn’t make any mention of opium. But the Opium War wasn’t really about opium anyway. It was a watershed event that signaled a new era—one of humiliation and painful adaption in a world in which China could no longer see itself as the center of the world.

Curiously, the treaty didn’t make any mention of opium. But the Opium War wasn’t really about opium anyway. It was a watershed event that signaled a new era—one of humiliation and painful adaption in a world in which China could no longer see itself as the center of the world.

Despite more than 300 years of direct contact with the West, China failed to learn almost anything about them. The Manchu court was appallingly ignorant, holding on to ludicrous beliefs (for example, that the accuracy of British warship cannons was due to sorcery).

Economically, politically, and psychologically, the war had a devastating effect. It undermined the longstanding notion that China was the most advanced and powerful country in the world. Doubts came up about whether the Qing had lost the Mandate of Heaven…

1850-1864: THE TAIPING REBELLION

The Taiping Rebellion was an odd affair— one that would send a severe shock to the Manchus and altered the balance of power between the Chinese and Manchu rulers.

Fueled by growing Anti-Manchu feelings, a peasant rebellion—following a long tradition of secret societies—broke out in southern China. They had early successes (taking Nanjing in 1853) but then lost momentum under the poor (and arguably mentally-ill) leadership of Hong Xiuquan.

Fueled by growing Anti-Manchu feelings, a peasant rebellion—following a long tradition of secret societies—broke out in southern China. They had early successes (taking Nanjing in 1853) but then lost momentum under the poor (and arguably mentally-ill) leadership of Hong Xiuquan.

The rebellion might have had a chance to defeat the weakened Qing, but Western powers didn’t join forces since they lacked confidence in Hong (who preached the Ten Commandments and claimed that he was the younger brother of Jesus Christ). Their religious fanaticism was curious and off-putting to the Chinese as well (they preached abstention even though Hong had a personal harem of 88 concubines).

1856-1860: THE SECOND OPIUM WAR (the “Arrow War”)

Following escalating demands from foreign interests, another flare up breaks out. The Qing are humbled again, but not before British and French forces loot and burn the Summer Palace in Beijing. New peace treaties forced upon Qing court: Kowloon is ceded to the British in addition to indemnities. European powers divide parts of China into their “spheres of influence”.

1864: THE TAIPING REBELLION FINALLY ENDS

After Western nations swing their support to the Qing, the rebellion ends with the Qing recapturing Nanjing, whereby Hong kills himself. It was a bloody affair— before the rebellion was over, an estimated 20-40 million people died, a death toll far exceeding that of the nearly contemporaneous American Civil War.

THE “SELF-STRENGTHENING” MOVEMENT

By now Qing rulers are (mostly) out of denial and start to get with the times. With the help of Western powers—who are surprisingly generous in sharing many technological secrets—China starts modernizing. For instance, shipbuilding and machine factories are constructed and Chinese students are sent abroad to study Western languages and science.

NEXT: More bad news for the Qing >>

Return to Chinese History Timeline

Return to China Mike’s Home Page

![The Ming Dynasty [1368-1644 ]](https://www.china-mike.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/ming-dynasty-map-small.jpg)

![THE QING DYNASTY [1644-1912 ]: Part I](https://www.china-mike.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/qing-dynasty-map.png)