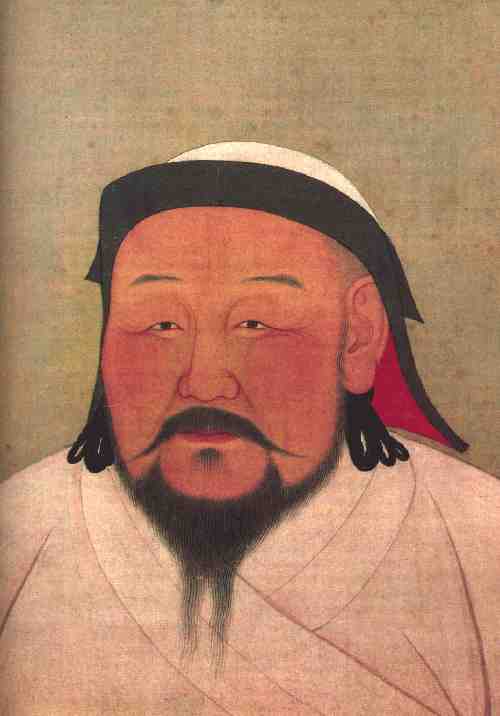

Kublai Khan, the first Mongol ruler of a unified China, moves his capital to Dadu (today’s Beijing).

Not satisfied with China, he continues aggressive fighting overseas—ruling as far as India and Korea (but wasn’t able to take Japan). Under the Yuan, China controlled the largest territory in their history. Ironically, modern day China’s claim over Tibet dates back to this period, when China itself was ruled by non-Chinese foreigners (some say it’s not a true “dynasty” but instead a foreign “occupation”).

The Mongol conquest was a turning point in Chinese civilization. Up to this point, it had more or less been a continuous development—peaking under the Song. Although Yuan was (relatively) short—lasting less than a century—it left a deep impression on Chinese psyche. Chinese culture lost its vitality and became more introverted. And it would start of a long tradition of being suspicious of foreigners.

After taking China, some of Kublai Khan’s advisers counsel him that the Han Chinese were of no use and should all be killed. But he realizes that he can tax them. And so for the next century, they are mercilessly squeezed out of every ounce of silver, silk and grain possible.

The Mongols also eliminate imperial exams and revive the Silk Road, once again connecting China to the Middle East and Europe. The Grand Canal is extended, in addition to an impressive network of highways.

Great Traveler or Great Imposter

Marco Polo (1254-1324) claimed to have worked under the service of Kublai Khan for some 17 years. However, historians today debate whether he even set foot in China or just cobbled together tales from other travelers during his voyages. It was supposedly Beijing under Mongol rule when observed strange long noodles, black rocks used as fuel, and money made of paper, as well as massive cities that dwarfed any in Europe. But in addition to some historical inconsistencies, he failed to mention some obvious Chinese phenomenon like the Great Wall, foot-binding, or tea.

1337: Start of Great Bubonic Plague, which devastates Eurasia and enters China from the northern steppes.

1340-60s: The Mongol Empire is in decline, after losing touch with their warrior roots and split by internal fighting (once again, from a lack of clear succession). Ever unpopular among the Chinese, discontent brews stronger. After the Yellow River bursts—and Yuan court takes no action, leaving millions die—many are committed to rebellion.

Peasant uprisings—inspired by successes of the White Lotus secret society andthe Red Turban Rebellion—spread across China. They eventually defeat the Mongols in 1368, led by a commoner named Zhu Yuanzhang. The rebel leader declares himself the emperor of a new dynasty, the MING (“luminous” or “bright”)— becoming the first commoner in 1500 years to ascend to the imperial throne. He gives himself the title of Emperor Hongwu (“Vastly Martial”).

![THE SONG DYNASTY [960-1279 ]](https://www.china-mike.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/song-dynasty-Bianjing-city-gate-small.jpg)

![The Ming Dynasty [1368-1644 ]](https://www.china-mike.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/ming-dynasty-map-small.jpg)