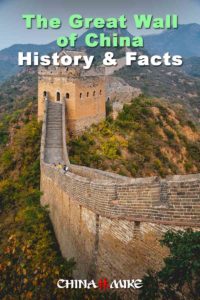

The Great Wall of China has a rich history in Chinese culture. In this post, you will learn the history & facts of The Great Wall of China how it was built and why, including the length and the dynasties that built it.

Anybody who is familiar with China is aware of The Great Wall. Beloved Chinese leader Mao ZeDone even quipped that “He who has not climbed the Great Wall is not a true man”. But while most people are aware that a massive wall exists, very few are familiar with the The Great Wall of China history and facts.

For this reason, we’re going to dive into a brief history of the Great Wall: who built it, why they built it, how it eventually failed at the job for which it was created, and a few other interesting facts along the way.

Who Were These Invading Nomads?

To understand this, we need to first understand why The Great Wall was built. Most Great Wall histories tell us that it was built in order to keep out “nomadic tribes from the north”. But who were they exactly?

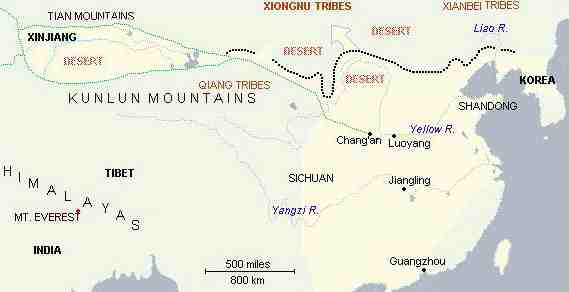

Nearly half of Modern China is desert, mountain or arid plateau, particularly in the north. Throughout China’s history, the people from these unforgiving “northern steppe” areas lived in close proximity (often overlapping territories) with the Chinese. These northern nomads were certainly not all homogenous, however they shared many similarities and had distinctively different cultures and languages from the Chinese.

For over 2,000 years—they regularly harassed, invaded and even conquered the settled agricultural civilizations of the Chinese Empire.

Today, historians debate the reasons for this complex, dynamic interaction. However, throughout history, the Chinese have typically resorted to simplistic explanations: These nomads are just naturally uncivilized and warlike (even sub-human).

For instance, a Han Dynasty historian wrote that the northern Xiongnu simply had an inborn nature towards plundering and marauding (which is almost as overly simplistic as saying that modern terrorists attack us because they “hate our freedom”).

Settled Agriculture vs Nomadic Herding

Modern historians, however, focus on the fundamental incompatibility between settled agriculture and nomadic herding. The theory is that conflict between the two types of civilizations should not be surprising given their close proximity.

If, for instance, drought or famine hit the northern steppes, the nomads were forced to find pastures in Han Chinese territory…inevitably leading to conflict. Or in truly desperate times, they might resort to pillaging Chinese settlements.

This must have been a tempting option given their far superior skills on horseback, which included exceptional skill in mounted archery (they typically were trained on horseback from an early age).

For these early “shock and awe” warriors, they could swoop in…..and just as easily escape without the threat of being chased down and caught.

To Trade or Raid – That Is the Question

Historians also look at the dynamic of these two cultures through the lens of trade. Through the centuries, the relationship certainly wasn’t always antagonistic—they often co-existed peacefully and engaged in mutually beneficial trade.

For instance, the northern nomads valued grain, textiles, medicines, pottery, and metal tools (including weapons). On the other hand, the Chinese lands weren’t well suited for raising horses—essential for mounted cavalry to fight each other as well as the nomads. There was also a strong Chinese demand for pelts, cattle and sheep.

However, during periods when trade relations were cut off, the nomads had the option of simply smashing and grabbing.

Persistent Headache for Chinese Emperors

These nomadic tribes weren’t just small groups on sporadic raids either. Some were formidable enough to conquer and rule China– the Mongols ruled for a century starting in 1279, and the Manchus for nearly two and a half centuries starting in 1644.

As a result, for over 2,000 years, successive Chinese emperors were preoccupied with containing their northern neighbors. Their solutions ranged from a mix of diplomatic and military options.

For particularly strong dynasties, the military option was sometimes successful. For instance, the Han Emperor Wudi led some successful attacks into the Xiongnu homelands in 119 BC. But these campaigns were costly and their inferior skills on horseback always put them at a disadvantage, whether fighting or chasing.

Historians also note that these persistent problems with their neighbors helped shape a sense of Chinese cultural superiority. This was evident as early as 3,000 years ago, when today’s Chinese name for “China” was first used during the Zhou Dynasty, 1066-771 BC (Zhong Guo: 中国, literally “Central Nation” or “Middle Kingdom”). All outsiders were lumped into the “uncivilized barbarians” category, an attitude that would persist through the early 20th century (actually, there’s still a sense of cultural superiority in China today).

The Great Wall of China History 1.0

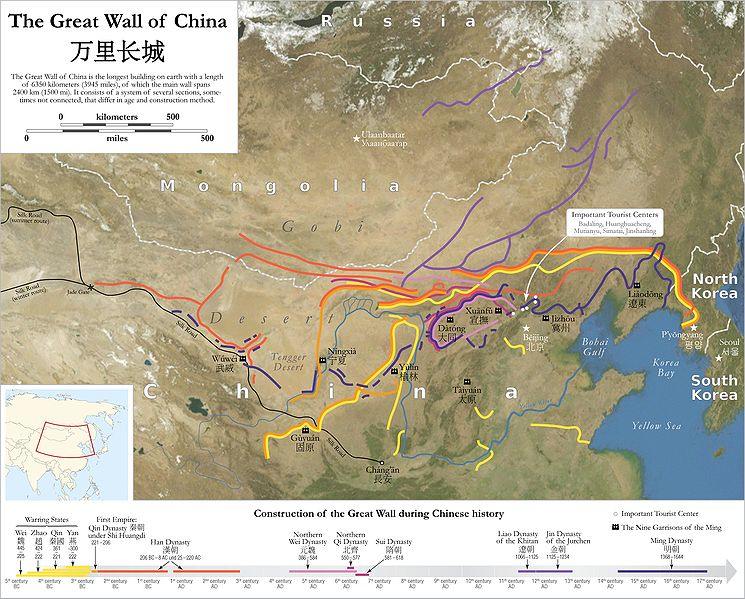

As mentioned in the overview, large-scale wall building started during the Warring States Period (475-221BC). During the Qin Dynasty, some of these early fortifications along the northern frontier would become part of the “first” Great Wall.

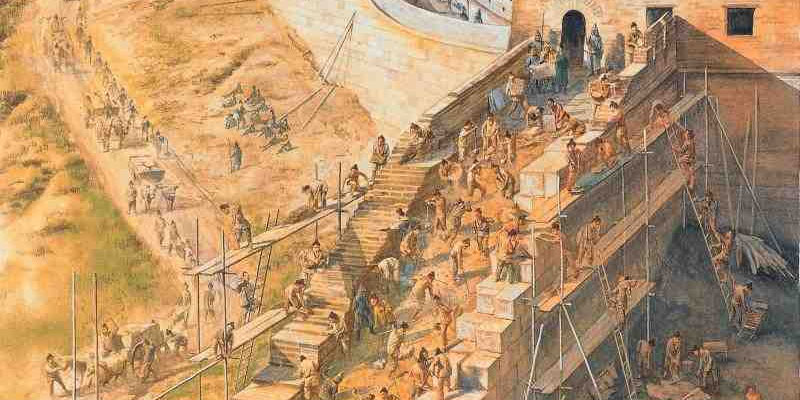

In 215 BC, the First Emperor Qin Shi Huang ordered his general Meng Tian to start constructing the Great Wall to protect against the northern nomads. In addition to building on previously constructed walls along the northern border, he also ordered the destruction of the earlier wall sections that now divided his empire along the old borders (to impose centralized rule as well as prevent any resurrection of regional warlords).

The first and most famous historical reference of the Great Wall is found in the Shi Ji, the first systematic Chinese historical text:

“After Qin had unified the world, Meng Tian was sent to command a host of 300,000…and built a great wall, constructing its defiles and passes according to the configuration of the terrain. It started at Lintao, crossed the Yellow River, wound northwards touching Mount Yang and extended to Liaodong, reaching a distance of more than 10,000 li.”

This brief passage hit two key phrases that gave the Great Wall its name. The first was chang cheng (“long wall” or “great wall”). The second was wan li, or “10,000 li” (li = a unit of distance about a half a kilometer or third of a mile).

Though the distance isn’t meant to be literal, the Chinese today refer to the Great Wall as wan li chang cheng (usually abbreviated to just chang cheng). In ancient China, “10,000 li” was often used as a shorthand for “infinity”.

Besides the Qin, the other two major wall-building dynasties were the Han Dynasty (206BC-220AD) and the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).

The Great Wall Under The Han Dynasty

The short-lived Qin dynasty was followed by the Han Dynasty, which lasted for over four centuries at its capital of Chang’an (today’s Xi’an). Building on the Qin walls, the Han invested a lot into fortifying the Great Wall with towers and other defenses (in order to “stop the Hu horses crossing the Yinshan mountains,” in the words of the time).

The Han significantly extended the Wall out to the Gobi Desert—due largely to their westward expansion of the Silk Road (the Wall protected traders from roving bandits). In fact, the Han-era Wall—stretching from Liaodong in the east all the way to the region of Xinjiang to the west, was the longest wall built by any dynasty.

After the Han, the Wall mostly fell into disuse (mainly because it was costly to constantly maintain and repair it). Future emperors often relied on a combination of alliances, good diplomacy, and a strong military to keep their northern neighbors in check.

For instance, a Tang Dynasty (618-907) emperor stated that one of his generals was “a better Great Wall than the ramparts built by the Sui emperor Yangdi” (the previous dynasty).

The Great Wall Serves as a Trading Market?

Throughout the Great Wall of China history—when relations weren’t overly antagonistic—the Wall served as trading markets for the different cultures to meet and trade goods.

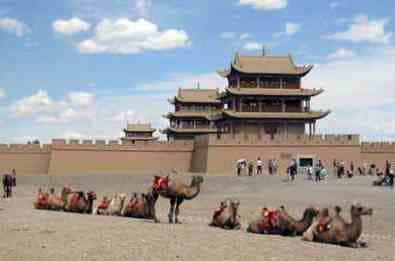

After years of these economic and cultural exchanges along various passes along the Wall, entire cities sprouted up with residents from both sides, including at Shanhaiguan Pass, Zhangjiakou, Gubeikou, and Jiayuguan Pass.

The Mongol Threat to China

Fast forward to the 1200s. During the Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279), China saw the rise of a new breed of ferocious steppe warriors: the Mongols. Led by the legendary Genghis Khan, the Mongolian Empire united the northern states to become a large, formidable, and well-organized army that was more than capable of threatening the entire Chinese Empire.

Despite significant fortifications, the Wall at the time was still largely the earthen walls of past centuries and relatively easy to overcome. Khan and his Mongol horde easily passed through at the strategically located Juyongguan Pass in 1211. They plundered at will around the capital of Beijing, though didn’t attempt to sack it.

In the following decades, the Mongols regularly found ways around or through the Wall. In 1279, the Mongols—under the leadership of Kublai Khan, Genghis’ grandson—defeated the Song and ruled all of China for the next 100 years (the Yuan Dynasty). As expected, the Walls were not maintained during the Yuan Dynasty since there was no longer any northern threat to repel.

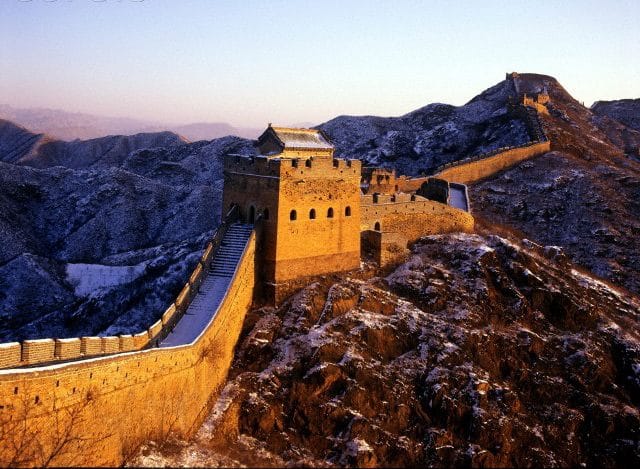

The Big, Bag Ming Dynasty Walls

Fast forward a century later: The Chinese regained power in 1368, after they drove the Mongols back north—signaling the start of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). All of the modern sections of the wall (that you typically see in photos) were all created during the Ming Dynasty.

With the threat of the Mongol still fresh in mind, the Ming government naturally spent a lot of time thinking about border policies and defenses (as well as diplomatic strategy).

Building a new wall, however, caused a lot of debate– many officials believed that building and maintaining a new wall would simply be too costly. Also, because of early successes in fighting the Mongols in their own territory, the project was shelved until the 1400s, after relations with the Mongols deteriorated.

An interesting note: the official Ming documents didn’t refer to the “chang cheng” since it was still so firmly associated in Chinese folklore with the widespread suffering caused by the much hated First Emperor Qin fifteen centuries earlier. Instead, it was referred to as the “bian cheng” (“frontier wall”).

Eventually, the Ming rulers decided to start construction of a new, impregnable wall. They also came to the conclusion that more than walls were needed – military outposts near the northern border would be the first line of defense against invaders. These so-called “nine outer garrisons” were the base of operations for a military community, whose purpose was defensive as well as diplomatic. The second, inner line of defense consisted of earlier walls, which were linked by new walls and forts built at mountain passes.

The Ming-era walls took over 100 years to complete (though not always continuous given constant political infighting). By the end of the 16th century, the Great Wall 2.0 was mostly completed–these Ming Walls are undisputedly the zenith of the Great Wall construction.

The Manchus Come Marching In (Come On In!)

After nearly three hundred years, the Ming Dynasty came to a close in 1644 after collapsing from corruption, ineffectiveness, and ultimately internal rebellion. The Ming was followed by the Qing Dynasty. Like the Yuan Dynasty (Mongols), the Qing was a non-Chinese state from the north, called the Manchurians.

Unlike the Mongols however, the Manchus came into power through the back door. In 1644, the weakened Ming government was quickly being overrun by a peasant-led rebellion. At the same time, the Manchus—who coexisted relatively peacefully with the Ming—saw their opening and marched their army to the gates of the Great Wall at “The First Pass Under Heaven” (aka, Shanhaiguan).

The Ming general in charge of Shanhaiguan was caught with a dilemma: He ultimately decided that they couldn’t defeat the rebellion alone so he allied with the Manchus. He opened the gates and allowed them to march through. The Manchus marched to Beijing, helped defeat the rebels, and then declared the start of a new dynasty: the Qing Dynasty.

Great Wall historians like to point out that it’s ironic the Ming spent over a century building the Wall to defend against Mongol invasion…only to let another group of northern foreigners simply march through and take over.

The Great Wall After the Ming

During the Qing Dynasty, the Great Wall fell into disrepair (again). For one, there no longer was any threat from the northern steppe people…the Qing rulers were from there (and had good relations with the other northern states).

More importantly, they would soon have their hands full with a new threat arriving by sea; the maritime powers of Europe as well as an increasingly powerful and aggressive Japan.

Japanese Invasion | Great Wall of China History & Facts

It wasn’t until the 1930s that the Great Wall played any significant role in Chinese history. During (and before) the second Sino-Japanese War of 1937-45, the United Chinese Front (Nationalists and Communists) actually used the Great Wall for its intended purpose as a physical barrier to defend from northern invasion (what are the chances!).

At the time, Japan had control of the areas north of the Wall, in Manchuria. When Japanese troops marched south to attack Beijing in 1933, they encountered an unexpected obstacle: a curiously long wall blocking their path. Most of the fighting was concentrated near Shanhaiguan (where the Manchus marched through).

After three days of intense fighting, the more modern and well-oiled Japanese troops broke through. Today, thousands of bullet holes can be seen along the Wall from battles against the Japanese.

Twelve years later, Shanhaiguan and the Japanese would again make history at the Great Wall. Despite the fact that Japan had just lost WWII and formally surrendered 1945, the remaining Japanese troops who were hunkered down there refused to lay down their arms (perhaps because of their “never give up” samurai honor code). On August 30, 1945, the Chinese—supported by shellfire from the Soviet Red Army—supposedly killed 3,000 Japanese soldiers in the span of three hours.

The Great Wall Under Communist China

For three centuries after the Ming dynasty collapsed, Chinese intellectuals tended to view the Wall as a symbol of what was wrong with China. They often said that it was a colossal waste of lives and resources that was less a symbol of the country’s strength than one of China’s crippling sense of insecurity.

As a result, the Wall has only been viewed as a cultural treasure in relatively modern Chinese history. Although it was Chairman Mao Zedong who once said: “You’re not a real man if you haven’t climbed the Great Wall,” his Communist revolution did nothing for the preservation of the wall.

On the contrary, the Great Wall—like so many destroyed ancient Chinese temples, relics, and art—were denounced as old symbols of feudalism that were holding China back. In the 1960s, Mao’s Red Guards carried this disdain to revolutionary excess, destroying sections the “feudal relic”.

Even before the Cultural Revolution and Red Guards, Mao also actively encouraged farmers to use make use of stones and bricks from the wall as free construction material. During the Mao era (and even beyond), peasants pilfered tamped earth from the ramparts to replenish their fields, and stones to build houses, walls, and country outhouses.

Fortunately Deng Xiaoping–Mao’s more practical successor—understood the Wall’s iconic value. In 1984, he famously declared: “Love China, Restore the Great Wall,” and launched a restoration and reconstruction effort starting at the sections near Beijing (Badaling was the first to undergo major restoration).

Perhaps Deng sensed that the nation he hoped to build into a superpower needed to reclaim the legacy of a China whose ingenuity had built one of the world’s greatest wonders.

The Great Wall Under Seige (Again)

Despite Deng’s efforts, the Great Wall today is still under assault by both man and nature (particularly in heavily polluted areas). Though no one knows for sure, Chinese Great Wall authorities have estimated that more than two-thirds of the Wall may have been damaged or destroyed, while the rest remains under siege.

Today’s threats come from reckless tourists, opportunistic developers, an indifferent public and the ravages of nature. Taken together, these forces—largely byproducts of China’s economic boom—imperil the wall, from its tamped-earth ramparts in the western deserts to its majestic stone fortifications spanning the forested hills north of Beijing, near Badaling, where several million tourists converge each year.

The Great Wall has been a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage site since 1987. However, many locals who live close to the Wall still view it with indifference.

According to William Lindesay, the founder and director of International Friends of the Great Wall: “The next 30 years are going to be a period where destruction of the wall is going to be much, much less.”

The British geographer was the first foreigners to run the length of the Wall (and was arrested several times in the process, including being deported). Commenting on the preservation of the Wall, he wrote: “Even into the 1990s, I have seen farmers with hoes dismantling towers, putting the bricks in their baskets to carry downhill for building.”

More stringent regulations were enacted in late 2006 to curb such abuses—damaging the wall is now a criminal offense. Anyone caught bulldozing sections or conducting all-night raves on its ramparts—two of many indignities the wall has suffered—now faces fines. The laws, however, contain no provisions for extra personnel or funds. According to Dong Yaohui, president of the China Great Wall Society, “The problem is not lack of laws, but failure to put them into practice.”

As recently as 2009, Mongolian gold prospectors irreparably damaged about 300 feet of a 2,000-year section of the wall in a remote part of Inner Mongolia. In 2006, a construction firm was fined Y500,000 (about US$63,000) for intentionally damaging the wall in order to build a highway through a large section of it without government approval, despite several warnings.

“The Great Wall is a miracle, a cultural achievement not just for China but for humanity,” added Dong Yaohui. “If we let it get damaged beyond repair in just one or two generations, it will be our lasting shame.”