For years, China’s one child policy has limited the population growth in China, but all of that is beginning to change.

The Chinese government says that the One Child Policy has restrained China’s mushrooming population (claiming that it has prevented an estimated 400 million births since it’s inception in 1980).

But critics say that the law is a violation of basic human rights enforced by heartless bureaucrats.

Here we’re going to discuss the history of China’s one child policy as well as various facts and FAQs that most people end up asking.

Brief History of China’s One Child Policy

To understand China’s one-child policy, we first need to take a step back in history to see where it all started.

1949 | The Commies Take Control

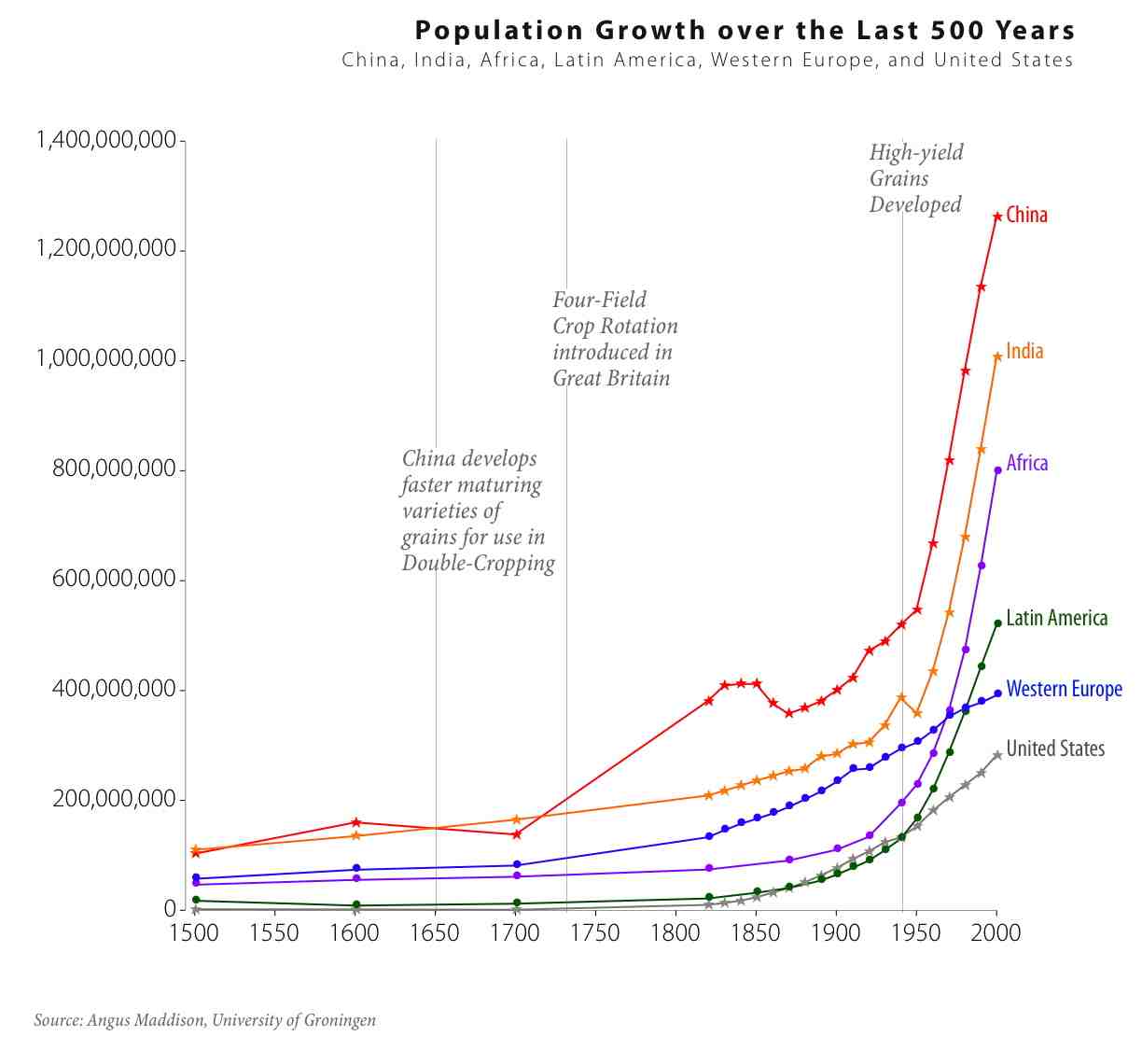

When Mao Zedong’s Communist Party took control of China in 1949, it inherited the most populous country on earth—over a half a billion Chinese people. This was more than triple the population of the U.S., which at the time stood at 150 million (US population in 2010 = 310 million).

More is better?

After a century of wars, unrest, and epidemics,China saw a population boom (helped by improved medical care and sanitation). This growth was initially greeted by leaders as an economic advantage. Reflecting the prevailing attitude of the leadership, Hu Yaobang, secretary of the Communist Youth League reasoned that, “A larger population means greater manpower…the force of 600 million liberated people is tens of thousands of times stronger than a nuclear explosion.”

The Communist Party of China (CCP) condemned birth control as well as banned the import of contraceptives (doh!).

Can China feed itself?

On August 1949, U.S. Secretary of State Dean Acheson authored the China White Paper, in which he expressed his doubts about China’s ability to feed itself. He wrote: “The first problem which every Chinese government has had to face is that of feeding its population. So far, none have succeeded.”

In direct response to this, a defiant Mao retorted: “Even if China’s population multiplies many times, she is fully capable of finding a solution; the solution is production.” He also famously stated that a large population is “a very good thing … Of all things in the world, people are the most precious.”

1950s – 1960s | The Sh*t Hits the Fan

It wasn’t long before Mao was proved wrong (one of many, many things he got wrong). In a few short years, China’s population growth started taking a toll on the nation’s food supply.

By the mid-1950’s, the government started to change their tune—providing contraceptives, developing voluntary birth control programs, and supporting abortion.

Meanwhile, Mao seemed to cling to the idea that a bigger population was advantageous. According to a 1965 Life Magazine article on China’s growing nuclear power. Mao told a visiting Yugoslav in 1957:

We aren’t afraid of atomic bombs. What if they killed even 300 million [Chinese]? We would still have plenty more–China would be the last country to die‘.

Mao Zedong

1958: The Great Leap Forward — Mao’s disastrous attempt to rapidly convert China into a modern industrialized state—took things from bad to worse. Botched state planning (such as shifting too many workers away from farming to steel production)—in addition to a series of ill-timed floods and droughts—resulted in nationwide food shortages. From 1958 to 1961, an estimated 20-30 million Chinese people starved to death. In short, a Massive Leap Backwards.

In the aftermath of the colossal catastrophe, officials turned up the heat on a propaganda campaign to put the brakes on population growth (which was briefly interrupted by the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution in 1966 before resuming again in 1969).

According to Wang Feng, a demographer at the University of California, Irvine, China’s leadership used the population boom as a convenient scapegoat.

“It was mostly a problem of the economic system…not really a population issue,” he argued. “But the growing population actually made those problems more apparent. I think that drove the leadership to have a more forceful birth control program.”

1970’s: The population still mushrooms…

Things get better. Although the people weren’t starving, there were still widespread shortages of every conceivable consumer goods. Everything from soap and cloth to eggs and sugar was rationed.

But the population continued to swell. By the early 1970’s, China’s population passed the 800 million mark.

“Late, Long, and Few”

The CCP launched a soft-sell approach to curbing population growth. Under the slogan “Late, Long, and Few,” the voluntary family planning campaign advocated delaying marriage, having fewer children and increasing the number of years between children.

It works. From 1970 to 1976, the country’s fertility rate plunges by more than half—dropping from about six births per woman to less than three. But they weren’t out of the woods yet—the rate leveled off and the voluntary program was about to go mandatory.

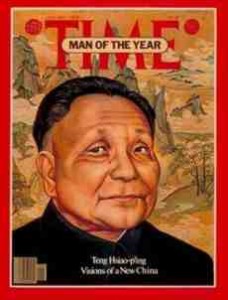

1976: Mao croaks. Enter Deng.

Mao dies and the baton is passed to Deng Xiaoping, who inherits a China in the poorhouse. With the political legitimacy of the post-Mao leadership on the line, Deng sets his sights on achieving what Mao’s planned economy was never able to deliver: a richer China.

The people were hungry—desperate—for a better life. Looking at their Asian neighbors—Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, and Singapore— Chinese leaders (and the people) knew how far back they were in terms of standard of living. And how is that measured? On a per capita basis. And of course, one way to boost that number is to reduce the denominator: the aggregate population.

1980: The gloves come off

The One Child Policy officially goes mandatory.

Under the original One Child Policy, couples needed to first obtain permission from local officials to have a baby (in 2002, they revised the law so that prior permission for the first child is no longer required).

Although the policy was meant to be an emergency policy (the original document anticipated that it would be phased out in 20-30 years), the CCP has continued the policy despite significant changes in China’s economy and demography.

FAQ: China’s One Child Policy

Were there any exceptions to the law? Loopholes?

Yes, there are numerous exceptions to the policy. Contrary to popular myth, the policy isn’t a uniform, nationwide prohibition on multiple children. In fact, today the policy doesn’t even apply to the majority of Chinese citizens. In 2007, the National Population and Family Planning Commission estimated that the policy applies to only about 36% of China’s population.

The exact rules and enforcement vary by province and local area, however, the main exceptions include:

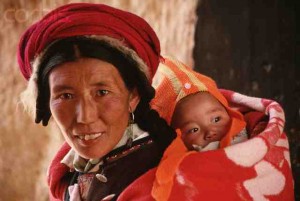

- Ethnic minorities. The policy doesn’t apply to China’s 55 or so ethnic minorities (such as Uighurs, Tibetans, and Kazakhs) who make up about 8% of China’s total population.

- Rural residents. Local officials in rural areas will typically permit a second child, especially if the first one is female (this revision came after massive protests in the early years by farmers who rely on children to help work the land).

- When both parents are only children (neither has any siblings), an allowance is typically made to have two children.

A notable exception was made after the devastating 8.0 magnitude earthquake in Sichuan province in May 2008. Of the nearly 70,000 people killed, an estimated 10,000 were children. Parents who lost their only child were legally allowed to have another child (similar exceptions are made in the case of deceased or seriously disabled children).

Though not technically “exceptions,” there are other ways of circumventing the policy. For instance, wealthy parents can simply pay a hefty fine to legally register and raise their second or third child. Many other parents simply lie—secretly giving birth to multiple children and then sending them to live with relatives in the country (usually passing them off as nieces and nephews).

How did China enforce the one-child policy?

Enforcement of the one-child policy relies on combination of carrots and sticks.

First, the Incentives: Those who follow policy are awarded a “Certificate of Honor for Single-Child Parents” and given rewards in the form of longer maternity leave, interest-free loans, and other forms of social assistance and government subsidies such as better health care, state housing, and school enrollment. Government employees can receive an extra month salary each year until their child turns 14. Couples who delay marriage and having their first child are also eligible for similar benefits.

To boost compliance, the National Population and Family Planning Commission of China (NPFPC) offers free, universally accessible contraceptive. The New England Journal of Medicine estimated that more than 87% of China’s married women use contraception (compared to about one third in other developing countries).

Penalties (and enforcement) can vary depending on specific situation as well as by province and local municipality. Similarly, the law and penalties have continued to evolve (in general, becoming less draconian over the years).

However, for the vast majority of people caught breaking the law, the penalties are financial—large fines imposed (which vary by region but are typically several times the average annual income). For those unable or unwilling to pay the fine, more heavy-handed tactics can be applied, such as seizing property and houses, being dismissed from jobs, or having their kids pulled out of school. The system also makes it difficult to hide unregistered children (for example, the inability to apply for schooling, etc).

Although widely publicized in the media, the really draconian measures—such as forced sterilization or abortion—are relatively rare these days, the exception and not the rule. However, during the early days, these tactics were widespread, despite widespread resistance in the countryside (more on draconian tactics below).

What did the average Chinese person think about the one-child policy?

A surprising (to me anyway) number of Chinese people today actually support the one-child policy. Hard numbers are difficult to come by, but I think it’s safe to say that it was not well received in the beginning (in accordance to the Chinese tradition of having large families).

But according to a 2008 Pew Research poll (Global Attitudes Survey in China), today about three-in-four (76%) approve of the policy. China’s increasing wealth and urbanization has contributed greatly to the “natural” societal tendency towards smaller families. The poll support this, showing that approval of the policy is highest among those with higher incomes (85%) and those living in cities (84%).

Today, China’s current fertility rate (1.54 in 2010) is not far off compared to Hong Kong (1.04) and its wealthier Asian neighbors: Japan (1.20), South Korea (1.22), Taiwan (1.15), Singapore (1.10) [Source: CIA 2010 World Factbook].

Was China’s one-child policy effective?

The policy has undoubtedly slowed down the fertility rate. The Chinese government claims that the law has prevented an estimated 400 million births (about the combined population of the US and Canada).

As mentioned above, China’s fertility rate would have most likely dropped on its own, without the law, however, any accurate estimates are hard to come by.

So why is China still so populous?

In 1950, China had about 550 million people. In 1980, when the policy was first enacted, the population stood at around 980 million.

Today, China’s total population is about 1.33 billion (to be more precise, 1,330,141,295 in 2010, according to CIA World Factbook). That means that the country has added an average of 12 million people every year since the law went into effect (or the equivalent of the total population of Greece).

And according to projections from the United Nations’ Population Division, their population will peak in 2030 at about 1.46 billion.

So what’s the deal? After three decades of the policy (and lower fertility rates), why aren’t there fewer Chinese people?

There are a few reasons to explain this seeming disparity. The bottom line is that the policy has significantly slowed China’s population growth—without it, their population today would be far greater.

One factor in the China’s population boom has been a drastic improvement in standards of living. Naturally, this translates to longer life expectancy. Between the early 1950s and early 1970s, Chinese life expectancy increased by an average of 1.5 years EVERY YEAR. Taken together, that means a leap in life expectancy from below 40 years old to almost 70 years old. Similarly, better health care has resulted in a sharp decline in mortality (particularly infant mortality), resulting in a population explosion starting in the mid-20th century.

Another factor is the so-called “population momentum” effect. The architects behind the law never expected to slash the population at once. Instead, they understood that eventually, the millions of children that were already born before the policy would grow up and hit their reproductive years. With or without the policy, that generation would eventually start having kids faster than the smaller elderly population would die off.

Add in the various exceptions and loopholes (and non-compliance), and the net effect is a still-growing population.

Some good news though: The U.N. Population Division also projects that China’s population will be down to about 1.40 billion by 2050, and will then will start to lose about 20 million people every five years or so.

Click here for my article “China’s Population: A Looming Demographic Time Bomb”.

Controversies & Criticisms of China’s Policies

Needless to say, the One Child Policy hasn’t been without its critics. To most Westerners, it’s incomprehensible that a government could legislate how many children a family can have—something most consider a fundamental human right. Over the decades, the Chinese government has come under fire from both outside and inside their borders—accused of everything from reproductive and human rights issues to female infanticide.

These are the most frequent controversies and criticisms, of both the tactics employed as well as of the unintended negative social consequences:

Draconian human rights violations

The most serious and widely reported criticisms involve allegations of forced late-term abortions, forced sterilization, official harassment, beatings, and even forced eviction. Generally speaking, these abuses—while they do still occur—have grown less common throughout the years. These days, the draconian measures aren’t conducted on a national, systemic basis. Instead, they typically occur at the local level by local officials who want to “make their numbers” by any means necessary (unlike Americans who, in general, trust their local & state politicians more than “the Feds,” in China it’s just the opposite since the unelected local politicians are most likely to be corrupt and abusive).

In the face of growing resistance to the law, some local officials have turned to harsh enforcement tactics. For instance, there were reports in 2007 of government officials who took sledgehammers to some towns and threatened to whack holes in the homes of people who had failed to pay fines for having too many children. Around the same time, other officials reportedly forced pregnant women without birthing permits to have abortions.

These heavy-handed measures resulted in riots. Some 3,000 in Guangxi province took to the streets in 2007, burning government buildings and overturning cars. There were reports that many civilians and officials were killed (as usual, reliable statistics in China are hard to come by).

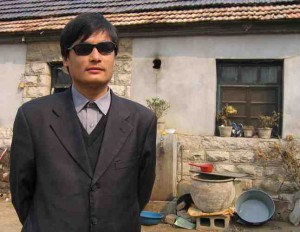

The most famous outspoken Chinese critic of policy is the so-called “blind lawyer”. A persistent thorn in the side of Chinese family planning officials, he drew international attention to the abuses, such as forced abortions and sterilizations. After being arrested, he made Time Magazine’s 2006 list of 100 People Shaping Our World. He spent over four years in prison and was released in September 2010 (but still remains under government surveillance).

Female infanticide and gender imbalance

Another widely publicized negative effect of the One Child law is the practice of female infanticide, the act of intentionally aborting female fetuses (and even infants). Even before the policy, the practice in China was not unheard of (although the practice was largely dropped by the 1950s). After the law went into effect, the practice became widespread.

Chinese culture has long had a strong cultural preference for boys to carry on the family name. According to long-standing tradition, once a daughter was married off, she would move in with her husband’s family and became responsible for taking care of her new family (unlike males who remain permanent family assets who can add a daughter-in-law, as well as grandchildren). Most of China’s rural residents have limited savings or pensions so need to rely on their children (traditionally many) to take care of them in old age.

Since the policy went into effect, China has had a significant gender imbalance, an abnormal sex ratio. The imbalance steadily grew worse since ultrasound became widely available in the mid-1980s. Today, the ratio hovers around 120 boys to 100 girls (compared to a “natural” ration of about 105 boys to 100 girls around the world). Although the practice is now illegal—China banned prenatal sex screening in 1994—the problem continues (it’s still fairly easy to pay a doctor to give more subtle “coded” message regarding a fetus’ gender—a slight shake of the head, for instance).

In rural areas, it’s not as common for parents to abort female fetuses if it’s their first time around since they’re allowed a second shot at a boy. But among second-born children in the countryside, there are approximately 160 boys born for every 100 girls.

Minister of the National Population and Family Planning Commission, Zhang Weiqing, said the government is committed to solving gender imbalance problem through with educational campaigns, increased punishments for sex-selective abortions as well as rewards (such as retirement pensions) for parents who have girls.

“This problem is a reality of country life in China,” said Zhang. “We have a 2,000-year feudal history that considered men superior to women, that gave boys the right to carry on the family name and allowed men to be emperors while women could not.”

Some good news: there’s increasing evidence that the pendulum is starting to swing the other way, in favor of girls, particularly among urban residents. According to a 2009 survey of 3,500 prospective parents in Shanghai, 12% said that they wanted a baby boy while 15% wanted a baby daughter (the rest stated no preference).

The reason for these changing attitudes? Economics and the law of supply and demand. For one, educational and career opportunities have greatly expanded for Chinese women in recent years, especially in the cities where the gap is rapidly closing (females are also capable of inheriting and running a family’s business). In short, urban daughters are now just as capable of taking care of parents (many parents also reason that a daughter would play the caretaker role better).

Also, the gender imbalance has made it much more difficult for Chinese men to get married. With such a vast supply of willing suitors, Chinese women have grown increasingly picky (I’ve personally heard many say that they won’t date any men who don’t own their own car and house…not a low hurdle in China). To marry off their sons, parents feel added pressure to buy them an apartment or a house (add rising real estate prices to the list). Unlike in the U.S., Chinese tradition also dictates that the son’s parents foot the bill for the wedding. All these factors add up to make the economics of having a boy less and less attractive.

Rapidly aging population & workforce challenges

Many have blamed the One Child Policy for China’s demographic problems. China’s rapidly aging population—combined with lower fertility rates—is expected to present significant social and economic challenges.

Demographers warn that the days of abundant, cheap Chinese labor is coming to an end. China is already seeing declining numbers of elementary school students and college entrance exam takers. According to one estimate, between 2010 and 2020, the total size of the China’s labor force aged 20-24 will be cut by 50 percent. In recent years, factories have already reported shortages of young workers—a problem bound to get worse before it gets better.

China’s average age will continue to grow dramatically. China’s median age was 32 in 2005. By 2050, that figure will leap to around 45, with a quarter of the population over 65. As a result, China will see a drastic change in their labor force: In 2007, China had six adults of working age for every retiree, but by 2040 that ratio is expected to drop to 2 to 1.

Again, traditionally, Chinese parents have relied on their children to take care of them in their older years. That looks unlikely to change much since the government’s pension system is almost nonexistent and social welfare systems are woefully inadequate.

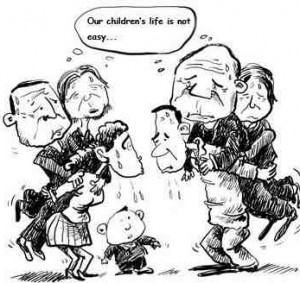

In short, one unintended but significant result of the One Child Policy is that it has eliminated the traditional support system of the extended family. Instead, the heavy burden will fall on the shoulder of only-children, who in many cases, will need to care for his/her parents in addition to four grandparents. The Chinese refer to this reverse-pyramid social phenomenon as the “four-two-one” problem.

Other Interesting Facts

Chinese Adoption

The United States is the No. 1 destination for Chinese children adopted abroad (about 80% are female; 25% are under the age of one). In 2007, China imposed new restrictions on foreign adoptions, barring applicants who are unmarried, over 50, obese, or who take certain medications.

The origins of the One Child Policy:

Song Jian, a missile scientist (not an economist or a demographer) was an unlikely key player in the decision to implement the policy. As a member of the strategic defense establishment, Song held the trust of top leaders. In her book, “Just One Child: Science and Policy in Deng’s China,” University of California, Irvine anthropologist Susan Greenhalgh writes how Song “wowed” the audience with high-tech computer projections—applying rocket-science formulas to population projections in advocating for strict birth controls. She noted that his rocket-science approach ignored real-life human consequences.

Secret two-child experiment:

In the mid-1980’s demographer Liang Zhongtang – a longtime critic of the one-child policy – convinced China’s leaders to run a “two-child policy” experiment in Yicheng, a country in northern China about 550 miles southwest of Beijing. The results?

In 2010, the Southern Weekend newspaper in Guangzhou revealed the details of the experiment for the first time: For the past 25 years, the experimental county’s population grew more slowly than the whole of China (about 20%, nearly 5 percentage points lower than the national average). Also promising: Yicheng’s gender ratio was in line with the natural norm at 106 males to every 100 females. In an interview, Liang was quoted as saying: “It shows the government could have had a looser child policy. Lower birth rates and slower population growth are inevitable results of economic development.”

Facts & Figures: One-Child Policy

As recently as 1965, Chinese women were bearing an average of six children. Today, that figure is down to 1.5 because of China’s One-Child Policy.

[ National Geographic cover “Population 7 billion” Jan. 2011 ]

The One-Child Policy only applies to about 45% of China’s population. Exceptions are made to have more than one child in the countryside, where 55% of China’s population lives.

[The Economist “The worldwide war on baby girls” March 4, 2010; CASS ]

There are numerous exceptions and variants on the One-Child Policy. In the coastal provinces, about 40% of rural couples are allowed to have a second if their first is a girl. In central and southern provinces, all couples are permitted a second child either if the first is a girl or if the parents suffer “hardship”. Ethnic minorities—such as those in Inner Mongolia and the far west—are exempted from the policy and can have multiple children.

[The Economist “The worldwide war on baby girls” March 4, 2010; CASS ]

Up to 3 million babies are hidden from the government every year because of the One-Child Policy, according to research by Liang Zhongtang, a demographer and former member of the expert committee of China’s National Population and Family Planning Commission.

[ The Telegraph UK “Chinese hiding three million babies a year” May 30, 2010 ]

China has a “wildly skewed sex ratio” with too few females, because of the One-Child Policy. China’s sex ratio for the generation born between 1985 and 1989 was 108 (already just outside the natural range of 103-106). Today, the ratio is over 120, which is “biologically impossible without human intervention”.

[ The Economist “ The worldwide war on baby girls” March 4, 2010 ]

By 2020, China will have 30-40 million more young men (under 19 years old) than young women, according to the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS). By 2020, “China faces the prospect of having the equivalent of the whole young male population of America, or almost twice that of Europe’s three largest countries, with little prospect of marriage, untethered to a home of their own and without the stake in society that marriage and children provide.”

[The Economist “The worldwide war on baby girls” March 4, 2010; CASS ]

By 2020, one in five young men in China will be brideless due to the “chronic shortage of potential spouses”, according to CASS. In the 20-39 age group, there will be 22 million more men than women….which is the equivalent of 10 cities the size of Houston populated exclusively by young males.

[Newsweek “Men Without Women” March 6, 2011 ]