The Chinese concept of “face” (aka 面子 or miànzi) refers to a cultural understanding of respect, honor and social standing. Actions or words that are disrespectful may cause somebody to “lose face” while gifts, awards and other respect-giving actions may “give face”.

It’s a complex concept that is important to grasp if you want to really understand Chinese culture. Here’s what you need to know.

Of all the idiosyncrasies of Chinese culture, the concept of “face” is perhaps most difficult for Westerns to fully grasp.

Because “saving face” is such a strong motivating force in China, it’s also one of the most important concepts in understanding the Chinese Mind.

As we dive deeper into this concept, we’re going to cover the following basics:

- Defining Face to a Western Audience

- Cultural Context of Face in China

- How to Operate within the Reality of Face

- Tips for Giving and Receiving Face in China

The goal in the end is that you’ll not only better understand the concept of face in China, but you’ll also be able to see how it influences the way you relate to people and do business in the country.

How Do You Define “Face” Exactly?

As a sociological construct, the Chinese concept of face is difficult to define.

The famous Chinese writer and translator Lin Yutang (1895 –1976) even went so far as to say that “face cannot be translated or defined.” He did, however, characterize it as “…abstract and intangible, it is yet the most delicate standard by which Chinese social intercourse is regulated.”

The closest translations are along the lines of “pride”, “dignity” or “prestige”.

But these don’t tell the whole story.

Face-management is much more than just impression management (or “protecting and enhancing your ego”) in the Western sense. Of course, no one — regardless of culture—wants to look bad or have their ego bruised. But the Chinese concept goes beyond the narrow Western concept of face (and is perhaps closer to the Arab concept of “honor”).

It’s also worth noting that the concept of face in China is vastly different than the concept of “guanxi” in China. Although both are equally important to understand.

Comparing Western Ego vs. Chinese Face

Unlike “Western face”– which is more self-oriented and individualistic — Chinese face is more other-directed and relational.

In other words, it’s less about your own personal pride or ego, and more about how one is viewed by others. Unlike Western face, Chinese face can be given or earned. It can also be taken away or lost.

Chinese face can be given or earned…it can also be taken away or lost.

As a general sociological statement, Western cultures tend to focus on the individual as an independent, self-reliant being. In raising children, the focus is on helping them develop a strong sense of personal integrity and individuality (misbehavior is often blamed on lack of self-esteem).

In contrast, for some 4,000 years, Chinese culture has downplayed the concept of the individual—instead emphasizing the supremacy of the family and group.

It was all about bringing honor to your clan. With the emphasis on the collective, the sense of self blurred so much that it practically didn’t exist. In fact, individualism was seen as immoral.

The point is that Chinese face can be communally created and owned. In 2008 study Cultural ‘Faces’ of Interpersonal Communication in the U.S. and China, Yvonne Chang of the University of Texas explains:

“Deeply rooted in the Chinese concept of face are conceptualizations of a competent person in Chinese society: one who defines and puts self in relation to others and who cultivates morality so that his or her conduct will not lose others’ face. This contrasts with the American cultural definition of a person who is expected to be independent, self- reliant, and successful. The end result is that a Chinese person is expected to be relationally or communally conscious whereas an American person is expected to be self-conscious.”

Guilt-Based vs Shame-Based Cultures

Without digging too deep sociologically, suffice it to say that this social phenomenon of face has a lot to do with the teachings of Confucius. He taught that if you lead people “with excellence and put them in their place through roles and ritual practices, in addition to developing a sense of shame, they will order themselves harmoniously.”

Here we see that the flip side of gaining honor is avoiding shame.

Thousands of years ago, China developed into a shame-based culture. This is in contrast to Western cultures, which are more “guilt” or “conscience-based”.

Generally speaking, the Chinese “behave properly” generally to avoid shame and they fear losing face—not necessarily because they might feel badly about their actions.

For many, anything goes….as long as you don’t get caught!

In China, shame isn’t just personal feelings—again, it’s a relationship-based thing that serves as a form of social control. Any sort of family or clan-kinship shame is covered up.

This is also in stark contrast to the US, where airing your dirty laundry and private business on talk shows is seen as socially acceptable (in general, the Chinese aren’t big on updating strangers on their menstrual cycles via Twitter).

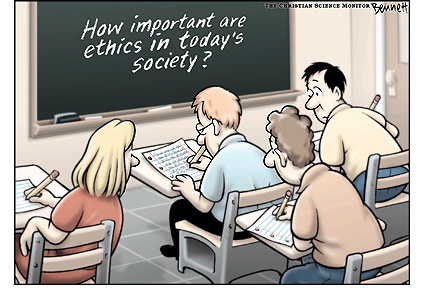

Ethics of “Face” in Relation to Truth

Western cultures tend to think in terms of “truth” and “rightness” (where being innocent and right is most important). Westerners are taught to respect objectivity and facts. The law applies equally to everyone the same and our behavior is something that should be directed by our consciences.

In the West, your honor or face is more about your personal integrity. We tend to admire the integrity of those who uncompromisingly face objective truth, regardless of how self-damaging the results may be.

In the US, you can admit and apologize for your shortcomings and gain respect for your honest efforts to learn from the past. Americans are generally forgiving if someone takes responsibility for their problems.

For instance, during his Presidential run, George W. Bush spoke openly about overcoming his addiction to alcohol. This is something that no Chinese official would ever do it—it would be a devastating loss of face and almost impossible to recover from.

In contrast, Chinese society has always functioned on basis of personal relationships rather than objective customs and laws. Indeed, the rule and laws laid down were often to serve those in power (and often arbitrary and ever-changing). Complicating matters, Confucian teachings say that you’re supposed to treat people differently depending your relative statuses.

As a result, Chinese “ethics” has never been based on universal principles of good and bad. Instead, they’re more based on the circumstances of the moment—a system that the West calls “situational ethics” (much to the chagrin of people doing business in China).

Similarly, the Chinese concept of the “truth” is not black or white either. The emphasis is less on always telling the objective “truth,” and more about what the situation and relationship calls for.

When it’s OK to Lie in China

In some ways, this helps explain the cultural differences on lying.

The Chinese will go through great lengths to protect face (their own as well as others). In fact, it’s perfectly acceptable to tell a lie—even a bald-faced one—if it serves to protect face.

China’s culture of shame doesn’t think of lies in terms of “right” and “wrong.” Instead, the goal of Chinese truth is often to protect the face of an individual, group, or even nation. In these situations, both parties can usually read between the lines and know when the “truth” is being re-packaged to help protect face (and they unfortunately will often assume that Westerners will know as well).

For instance, a hotel receptionist might tell you an obvious lie when he tells you that they don’t have any vacancies. This might be their face-saving way to avoid having to tell you that their hotel doesn’t allow foreigners.

Westerners often have a hard time with this. We don’t like to be bull-sh*tted. Our reaction is to call someone out on a lie. But in most cases, open confrontation is counter-productive, and will often result in denials or feigning ignorance.

So I’d recommend not backing your tour guide (or whoever) into a corner and calling them out if you catch them in a lie (it would be viewed as very rude, even cruel). In general, it’s a good idea to leave the Chinese with a way out of any potential face-losing situation.

Instead, if something goes wrong, always talk privately. Try to avoid assigning blame. And use the passive voice, as in: “IT seems as if there’s a problem.”

Flattery can often be very effective too: “I know this isn’t your fault but since you are very smart, what do you think we should do?”

Cultural Context to the Idea of “Face”

The concept of “face” in China is very much a cultural construct, therefore the best way to truly understand it is by seeing it within the context of Chinese society.

China’s “Super Girl Contest” Reality Show

For starters, we can look at the once hugely popular Chinese singing contest called Super Girl Contest, which is basically their version of “American Idol”.

Nearly half of the girls can sing English songs and the competition is just as intense as the US or UK versions….but their response to winning and losing tells us a lot about this Chinese concept of “face”.

Westerners will notice that a disproportionate amount of time of the three-hour show is spent with mutual emotional consoling by the singers, hosts and judges.

In fact, to protect against the shame of being eliminated, the show spends more time focusing on the losers rather than the winners!

And even though they had a version of the tough Simon Cowell in a judge named Wu Qixian, you won’t find him fighting with the other judges. Instead, it’s much more of a love-fest than American Idol—with everyone working hard to help protect face.

Unlike the “win-lose” zero-sum mentality of the US, Chinese reality shows and competitions also typically share the prize money.

For instance, in the 2006 show “Win in China” (the Chinese version of “The Apprentice”), the winner gets 10 million RMB. The runner up gets 7 million and the other three “losers” get 5 million each!

Chinese Idioms About “Face”

Illustrating the obsession with face-management, there are literally dozens of short sayings and proverbs, called Chinese Chengyu, that have to do with “face”.

These idioms give you some incredible cultural context into this idea of face in China.

“Men can’t live without face, trees can’t live without bark.”

人要脸树要皮 – rén yào lǐan, shù yào pí

“A family’s ugliness (misfortune) should never be publicly aired”

家丑不可外扬 – Jiāchǒu bùkě wàiyáng

“Face-Saving project”

面子工程 – Miànzi gōngchéng

For example, “That new expensive airport is just another face-saving project for local officials to suck up to their bosses.”

“Blacken one’s face”

往脸上抹黑 – Wǎng liǎn shàng mǒhēi

For example, “He blackened your face to get you back for what you did.”

A traditional insult is to say that someone “has no face”.

没有面子 – Méiyǒu miànzi

Similarly, one of the worst things is to “lose face”.

丢脸 – Diū liǎn

How to Operate within Chinese Face

So now that we understand how to define face and what it means within the context of Chinese culture, the next step is more actionable.

How can we make sure that we “give face” to our friends and colleagues and minimize the risk of “losing face”? Here are a few thoughts on how to operate within the reality of face in China.

How to Gain or Lose Face in China

Warning: Don’t treat this concept of face, or “mianzi”, too lightly. This is especially true if you’re doing business or spending a long time in China.

Foreigners working in China (who don’t appreciate the full cultural importance of face) often complain that their Chinese counterparts are “too sensitive” about being offended or having their feelings hurt.

Similarly, many ex-pats in China—as well as other Asian countries such as Japan, Korea, Thailand, Singapore—can tell you stories of how their local friend suddenly stopped talking to them (probably because they somehow caused them to lose face).

And from the Western perspective, it is true—the Chinese are generally more sensitive to any perceived slights having to do with losing face since it’s so ingrained in their culture. This thin-skin is largely a product of culture that has valued social harmony as the prime rule (and generally avoided criticism).

In the West, many of these slights are seen as minor and quickly forgotten. But in China, failing to appreciate face can cause serious problems.

While an American businessperson might be respected back home for his frankness and being a “straight-shooter,” he would likely be viewed in China as uncultured, overbearing, and rude.

For instance, an American subordinate attending a meeting where his boss is presenting would generally think nothing of raising a question, making an alternate suggestion, or even disagreeing in front of others.

In China, this would be a serious face-losing situation for the subordinate, boss, and even the company. In fact, making someone lose face can sometimes insult someone so deeply as to create an enemy for life.

Losing face can sometimes be so insulting as to create an enemy for life.

Indeed, revenge is very much part of the equation—and not just on Chinese soap operas, which include a heavy dose of avenging face-losing situations. I think it’s safe to say that throughout China’s long history, face has started many unnecessary conflicts.

In terms of practical China travel advice, a loss of face can result in some form of sabotage, non-compliance, or foot-dragging.

For instance, let’s say that you’re frustrated by an employee as you’re applying for a China visa in the US. You start ranting and raving loudly—demanding to see the manager, etc.

Don’t be surprised if your application is “lost” under the bottom of the pile.

Viewing China Through the Lens of “Face”

A better appreciation of face can go a long way in helping visitors better understand China.

For instance, foreigner business people will often notice that Chinese employees will often go to great lengths to steer clear of them. Most chalk it up to “being shy” or their inability to speak English.

That’s just part of it.

For the average Chinese person, talking to a foreigner is scary because it there’s a lot of potential for appearing incompetent and losing face, especially in front of other employees or the boss.

Even though they’re in their own country, many Chinese somehow feel that they’re supposed to know how to speak English when talking to a foreigner (instead of the other way around). Or even if they do speak it, there’s the fear that their English may not be understood, corrected or even laughed at (worse if they’re English majors and it’s part of their job description).

In general, the Chinese avoid situations when others can see them making “mistakes” (such as incorrect pronunciation).

While other Chinese people all know the ground rules governing face, they don’t know what they’ll get with a potentially unpredictable, emotional and loud laowai.

For better or worse, many Chinese have a perception that Westerners easily lose their cool and will fly off the handle at the drop of a hat. Worse, they might’ve personally witnessed or experienced past incidents where an angry foreigner exploded in frustration (leading to a loss of face for all parties involved).

Similarly, the average Chinese person on the street can also be apprehensive when being approached by a foreigner (asking for directions, taking a photo, making conversation, etc). In these situations, you can increase their comfort level by, well, not acting like a loud, back-slapping foreigner (yes, I’m looking at you Americans).

If you want to copy an American, I’d recommend taking John Wayne’s acting advice:

“Talk low, talk slow, and don’t talk too much.”

Pretend that you’re trying to feed a nut to a nervous squirrel–approach at an angle, don’t attract too much attention and no sudden moves.

Preserve China’s National Face

Operating under the construct of Chinese face goes way beyond just how you relate to family, friends and business contacts. In fact, many events in Chinese history can be better understood when viewed through the lens of Face.

All Chinese children learn about the incredible timline of Chinese history (through the CCP’s version of history nonetheless). The Chinese are keenly aware of their own history of “humiliations” at the hands of foreign powers.

This has resulted in a strong sense of nationalism—almost to the point of defensiveness and over-sensitivity.

On a practical level, avoid any criticisms that might be taken as disparaging (even about the government).

The 2008 Olympic opening ceremony is an obvious example of the importance of building up national face (you could say that it was the ultimate “face project” of modern China). It’s no wonder that they invested so much time and money in wowing the world. Not to mention the pressure on the actual athletes!.

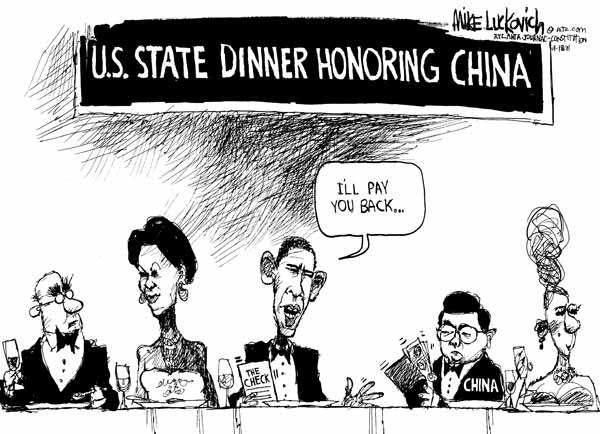

Example: Hu Jintao’s Visit to the U.S. in 2006

Even at the highest levels of government, failing to grasp the symbolic importance of Chinese face can cause problems, intentionally or otherwise.

Take the example of former Chinese President Hu Jintao’s 2006 visit to the US. Even though many of the mis-steps by the US and George W. Bush were probably unintentional, many Chinese netizens who got the real scoop believed that it was an intentional campaign to make China lose face on the international stage (especially since they spend so much thought into face when hosting foreign leaders).

President Hu had insisted on an official “state visit” (the highest form of diplomatic contact), which was given to his predecessor Jiang Zemin in 1997. President Bush didn’t give it to him, instead using the more neutral term “official visit” (Hu’s face was somewhat saved in the Chinese media by translating it as “state visit”). There was also wrangling before finally being given the full 21-gun salute, instead of the originally planned 19-gun salute.

Similarly, Hu was refused a full state dinner. Bush instead gave him only a state lunch (resulting in the fact that the meal wasn’t even reported in the Chinese media). During the greeting ceremony on the White House lawn, the loudspeaker introduced Hu as the president of “the Republic of China” (the official name of Taiwan), instead of the “People’s Republic of China”.

It gets worse. While Hu was giving his official speech, a protester from the banned Falun Gong group loudly heckled him from the stands. It took the Secret Service three minutes to escort her out.

The final act of humiliation occurred at the end as Hu started to leave the platform that he was standing on with Bush. As Hu was about to walk away in the wrong direction, Bush hastily reached out and grabbed Hu by his suit jacket to pull him back on the stand. If the scene occurred between only American politicians, it probably would’ve passed with little notice.

But from the Chinese point-of-view, it was deeply insulting to see their nation’s leader being tugged at and treated like a small child.

In fact, the whole affair was so disastrous from a Chinese face-losing perspective, that the Chinese state media downplayed the visit– preferring instead to focus on Hu’s visit to Bill Gates’ mansion and to Boeing’s massive facilities in Washington State.

In January 2011, Hu finally got his full state visit when he was invited to visit President Obama (along with the 21-gun salute and state dinner). According to Philip M. Nichols, a Wharton professor of legal studies and business ethics, the visit was “symbolically successful”—explaining that “One of the things the meeting accomplished was that President Obama treated President Hu—and by extension the People’s Republic of China—with respect.”

Another Example: 2010 Japanese Boat Incident

When I was living in China in September 2010, the Chinese state media was obsessively reporting on a two-week long spat between Japan and China. If not for face considerations, I doubt that the incident would have received all of the attention that it did.

If you know anything about Chinese history, you’ll know that the worst face-losing events were the Japanese invasions and occupations. Suffice it to say, there’s still very strong anti-Japanese sentiment in China (it’s very safe to say that they’re the most hated nation in China).

The basic incident: A Chinese trawler collided with a Japanese patrol boat in an area claimed by both countries. The Japanese coastguard let the crew go but arrested the captain. China responded with escalating threats and economic sanctions (even suspending Japan-bound shipments of rare earth metals crucial in advanced manufacturing).

Eventually, Japan let the captain go, although they didn’t give the apology that China demanded (after all, they have their own national face issues to deal with too).

Tips for Giving Face in China

Here are some simple tips to help “give face” to a business counterpart or friend in China.

- Praising someone publicly: This is true especially in front of their elders or boss.

- Giving high marks on customer evaluation forms: The Chinese are generally generous, especially when giving reviews of their teachers.

- Treating someone to an expensive meal or banquet: The most common face-giving technique that makes Chinese business and society run is the big banquet.

- Giving sincere compliments: Make sure that you’re showing that you’re enjoying yourself when being treated out.

- Giving an expensive gift: If possible, the best thing you can give is an imported gift that can’t easily be bought in China.

Avoid These Face-Losing Situations

If at all possible, try to avoid these particular face-losing situations with a Chinese counterpart:

- Openly criticizing, challenging, disagreeing with, or denying someone.

- Calling someone out on a lie.

- Not showing proper deference to elders or superiors.

- Turning down an invitation with an outright no (instead, they usually say “maybe”, “yes, maybe”, “we’ll do our best”, ” let’s think/talk about it later,” or “I need to discuss it with so-and so first”)

- Being late on a flimsy excuse (demonstrates that you don’t respect or take them seriously).

- Interrupting someone while they are talking.

- Being angry at someone –mutual loss of face for both parties

- Revealing someone’s lack of ability or knowledge (such as being able to speak English).