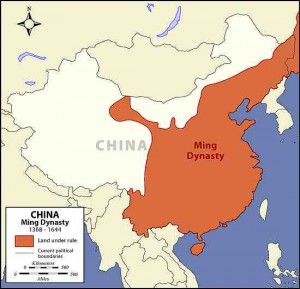

The Ming dynasty was one of the longest and most stable periods in Chinese history. Despite early naval explorations, the Ming dynasty was mostly inward-looking and insular—preferring to buffer China from the outside world.

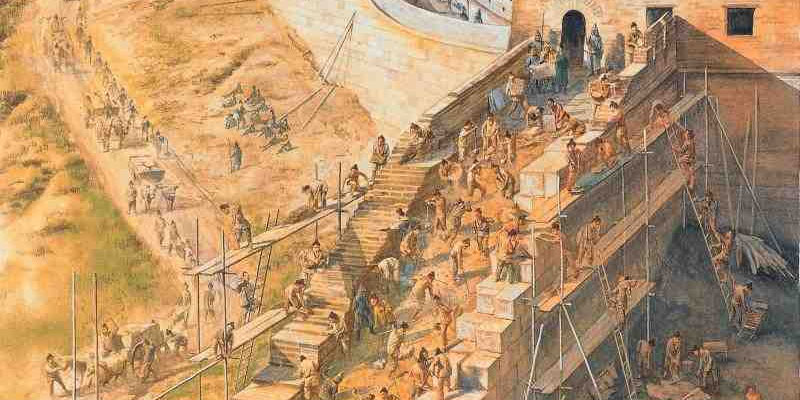

The best symbol of this was the Great Wall of China, which was extensively rebuilt and expanded during the Ming (the “modern” walls that we know today are all Ming-era). Another symbol of this detachment was The Forbidden City, where emperors shut themselves in and closed their eyes to new realities.

The Chinese Back In Charge

It was during this time in history that Europeans began colonizing the Americas. They would inevitably be drawn to China’s shores and make their mark on Chinese history. But they weren’t the only foreigners to hit the scene: Japanese pirates made their debut during this period, when they grew increasingly powerful and bold.

A Brief Moment of Naval Superiority

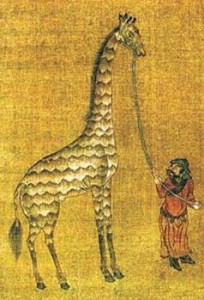

During the rule of Zhu Di (the Yongle emperor, 1403-24), China became the world’s most advanced sailors— with ships dwarfing those of contemporary Europe.

He sponsored the oceanic voyages of Zheng He, who commanded seven diplomatic voyages. Sailing with up to 300 ships and 20,000+ people (sailors, doctors, soldiers, translators), they embarked on legendary voyages to Southeast Asia, India, and Africa, among other previously uncharted areas.

1406: Yongle starts construction of The Forbidden City in Beijing.

1420: Construction of the Temple of Heaven starts in Beijing.

1421: Yongle moves the Ming capital from Nanjing to Beijing, where it has remained until today.

1450’s: Facing renewed aggression from northern neighbors, the Ming starts a 100+ year effort to connect and rebuild the Great Wall.

European Ships Reach China

Starting in the 16th century, European power in Asia grew—along with trade and their attempts to win Christian converts. The Catholic supremacist mindset of the early Portuguese adventurers regarded the “heathen” as inferior and expendable. Like their Dutch and English counterparts, many of these early sailors thought nothing of murdering their way to riches.

Not surprisingly, the Ming government—who were used to the gentler behavior of Arab and Indian merchants—tried to exclude or at least contain these “red haired” barbarians.

1514: Portuguese traders first land in China. They soon bought tea, which started catching on as a fashionable drink in European society. By 1550, Macau had effectively become their colony.

Trade developed gradually 16th and early 17th. Most problems were not with China, but instead resulted from rivalry between European powers.

1522: The Romance of the Three Kingdoms is published (I’m hoping for a spoof movie with Paul Rudd: “The Bromance of the Three Kingdoms“)

1540-60s: Raids by Japanese pirates intensify. In 1555, they venture as far up the Yangzi River as Nanjing, where the pillage at will for 10 weeks. In 1560, several thousand Japanese pirates land in Fujian province and loot for several months.

1600: China’s population exceeds 150 million.

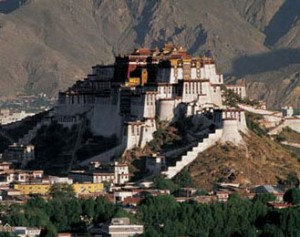

1642: In Tibet, the 5th Dalai Lama—nominally under Ming protection—asserts his temporal power and orders the construction of the Potala Palace in Lhasa.

Corruption, greed, and abuse progressively weaken the Ming (another familiar pattern). Peasant uprisings sprout up. Meanwhile, in the north, the (non-Chinese) Manchu become a serious threat.

1644: Rebels overtake Beijing whereupon the last Ming emperor hangs himself. Meanwhile, the Manchu armies of the north march towards the Great Wall, at Shanhaiguan (the First Pass Under Heaven). They encounter a Ming general who ultimately allies with the Manchus—allowing them to march through the gates towards Beijing. The Manchu take control and the Ming dynasty comes to an end.